Working from that belief that attention is a creative medium, I collaborated with Anna Riley in a 2023 Residency at The Corning Museum of Glass. We created a series of handmade glass devices inspired by the "Claude mirror," a pocket-sized, dark lens used by 17th-century artists. These devices are inherently beautiful objects as well as modes for focusing attention for viewing and interpreting the world around us.

Excerpts from an Interview with the Corning Museum of Glass

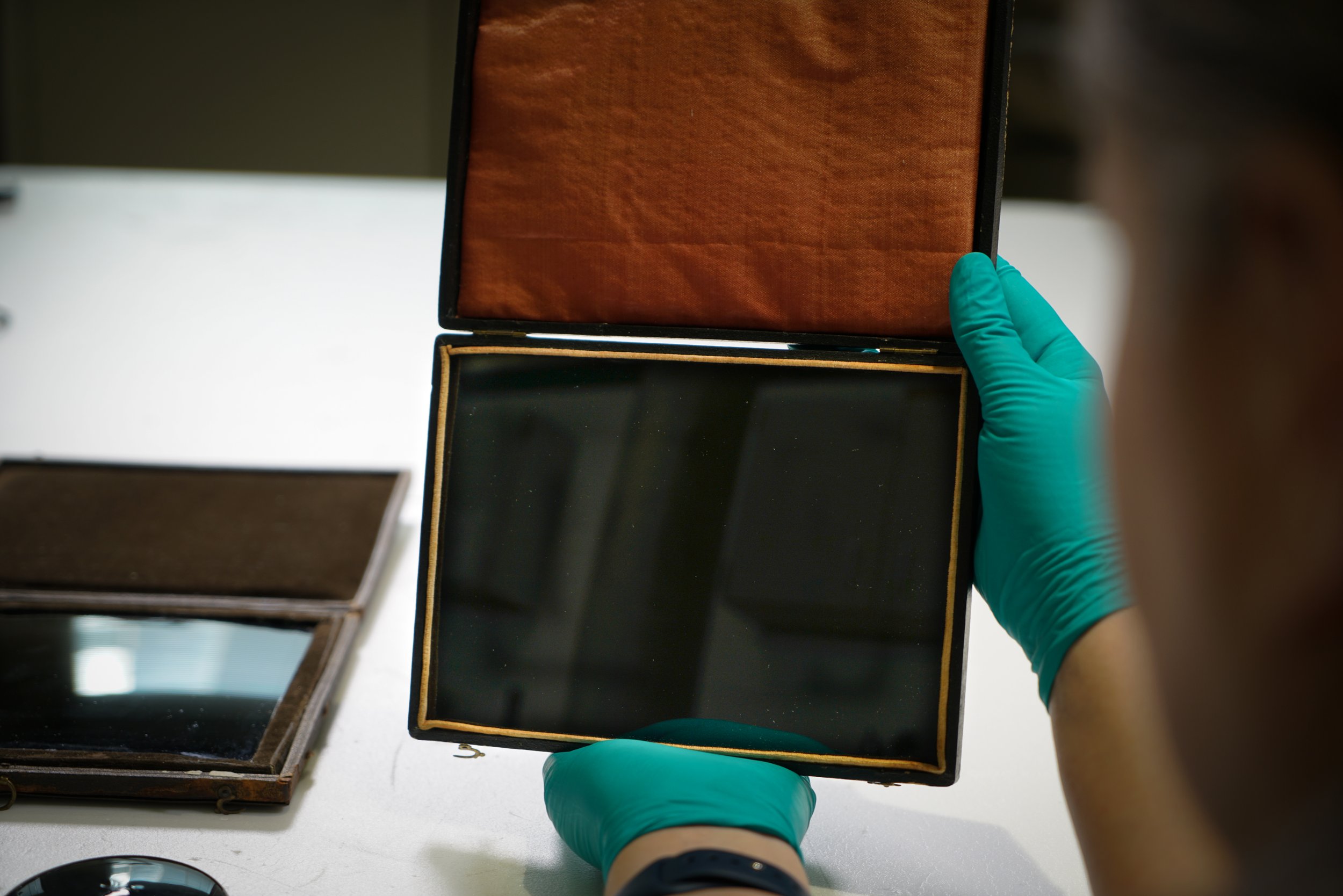

These devices were attributed to Claude Lorrain—a French painter in the 17th century. It is a handheld, portable device made from dark glass. Some are circular, others rectangular. Many of them were fitted into leather cases with a plush cloth lining to prevent scratches from marring their convex surfaces. The quality of the surface, of course, is key. An artist or traveler would carry this portable device to a notable vista, turn their back on the landscape, and hold the mirror up to see it in reflection. It is this peculiar choreography that interests us: turning your back on something in order to attend to it. We are reminded of the pervasive act of taking a selfie, say, in front of the Eiffel Tower or Vincent van Gogh’s A Starry Night. But we don’t use these examples in a pejorative way. We don’t see this action as wholly negative or needing to be rectified. Instead, we are curious: what is afforded by attending to something through this filter? And what is lost?

The black mirror as a symbol is clearly present today through popular media like the TV show. The black mirror feels analogous to the black box, a metaphor for the unknown inner workings of things, especially science and technology. Extant Claude mirrors in museum collections are often exhibited alongside other technologies, presented as items somewhere between artistic utensils and scientific instruments

Some of the earliest mirrors were dark—made of polished metal or obsidian, rather than clear glass backed with silver. This is why we were interested in CMoG’s obsidian mirrors, too, and we compared the surface quality of other mirrors to that of the Claude mirrors in Corning’s collection. The goal, of course, is not to compare one mirror surface as superior to another, but instead to observe the qualities of their reflections with curiosity. Sometimes an imperfect reflection can be more interesting and fruitful for creative work. In some of the objects you can feel a struggle between attending to the surface reflection and attending to the materiality of the thing itself. It’s hard not to be taken with the shimmering qualities of rainbow obsidian, as can be seen in this polished obsidian slab from Oregon.

Polished Obsidian Slab, 62.7.2A - Corning Museum of Glass

There are only a few in-depth written accounts of the Claude mirror. While we had an idea of how they might work, neither of us had ever seen one in person. It was important for us to get a sense of their reflective qualities. We were interested in the curve of the face, the depth of the black glass, as well as other details that may not have been mentioned within the historical records.

We were aware, coming into the residency, of a very well known black mirror in the Museum’s collection. Fred Wilson’s I Saw Othello’s Visage In His Mind (2013) draws attention to race, not just through Desdemona’s line, but also through the black glass itself as a material gesturing to the history of unrecognized black labor in the glass industry in Venice.

Fred Wilson’s I Saw Othello’s Visage In His Mind, 2016.3.6, is on display in the Contemporary Art + Design Galleries.

Our friend and colleague, Leonard Nalencz, joined us at the Museum to use these black mirrors (the ones we made) for sustained observation of Wilson’s To Die Upon a Kiss as well as Spencer Finch’s The Secret Life of Glass. Nalencz runs a non-profit called Project 404 that seeks to reclaim digital technologies as tools for harnessing our attention, rather than being ‘lulled into passivity,’ as he writes. Each participant had a different mirror—some glass, some obsidian. They ranged in size and shape, and all produced very different types of reflections. Our colleague Leonard wrote a lovely prompt for the practice: ‘What are you seeing: the object you are holding? The object you are beholding?’ It prompted our attention to flicker between the artwork we’d gathered around and the black mirror in our hands. And between the two—collected on the mirror’s surface—was the artwork’s reflection. We can’t speak to each person’s individual experience, but we both felt struck by the liveliness that the black mirror brought to the whole exercise.